Researchers climb world's largest giant sequoia, check for bark beetle infestation

You could say the General Sherman Tree was overdue for a physical—by at least 2,000 years.

The iconic giant sequoia, which stands in California’s Sequoia National Park, is the largest living tree on the planet and has withstood two millennia of storms, drought, and wildfires. But it has never had a proper check-up.

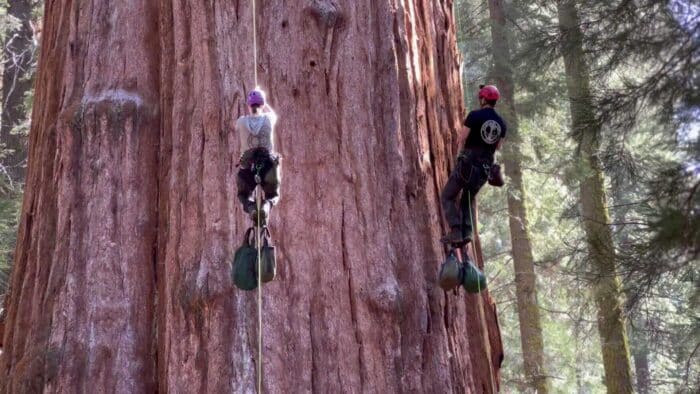

On May 21, researchers with the Ancient Forest Society used climbing ropes to ascend to General Sherman’s upper crown in the first-ever climb of the 275-foot-tall giant sequoia. Their mission: to visually inspect the ancient tree for signs of infestation by sequoia bark beetles—an emerging threat that has already killed as many as 40 mature giant sequoias since 2015.

“The deaths of these trees, each having lived for thousands of years, are the first recorded instances of giant sequoias being killed by insect attack ever,” said Clay Jordan, superintendent of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, speaking to reporters and members of the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition, which coordinated the health inspection.

Bark beetles an emerging threat to giant sequoias

Sequoia bark beetles are native to the Sierra Nevada and their activity has been noted near giant sequoia groves as far back as the 1920s. So why have these ancient trees succumbed to beetle infestation in only the last decade? Researchers believe that changing conditions—including severe drought and hotter temperatures—have weakened some of these colossal trees, making them less resistant to insects.

Typically, bark beetles attempting to bore into a giant sequoia are repelled by high concentrations of tannin—a natural chemical found in the tree’s hard outer bark, which can be up to two feet thick. But sequoias that are stressed or injured may be unable to mount this sort of counterattack. If beetles reach the tree’s soft cambium layer, they deposit their eggs in tunnel-like “galleries.” After hatching, the larvae eat their way through the vulnerable tissue, damaging or in some cases killing the tree.

“The biggest threat to giant sequoias continues to be high-intensity wildfire driven by fire suppression and climate change,” said Ben Blom, Save the Redwoods League’s director of stewardship and restoration. “Such fires have killed thousands of giant sequoias over the last five years—a loss of up to 20% of the mature trees. But it’s also important to study the impacts of bark beetles on giant sequoia mortality. We don’t want to be caught by surprise by a new threat.”

What General Sherman’s health check revealed

After descending from high in the canopy, Anthony Ambrose, executive director of the Ancient Forest Society, presented the team’s preliminary findings to the waiting crowd. The news was good. Although the researchers saw evidence of bark beetle activity in General Sherman’s branches—including attempted entry holes—“they don’t seem to be very successful,” said Ambrose. “The adults that are trying to burrow into the bark don’t seem to be making it very deep and in some cases where they do get down into the live bark, the tree seems to have pitched them out.”

Ambrose said that the team hadn’t found any live beetles or galleries and that the number of entry holes in the General Sherman Tree was very small compared to other sequoias they’ve examined. “It seems to be successfully fighting them off,” said Ambrose. “The tree seems to be very vigorous, the foliage is very health. It looks really good.”

In addition to the researchers’ direct observations, the health inspection also tested two other methods for detecting bark beetle activity: Drone imagery and remote satellite imagery. Both methods are considered to be more efficient and less invasive than tree climbing for determining if a sequoia is stressed or under beetle attack. The goal is to develop a model for rapid, large-scale monitoring of bark beetle attacks throughout the giant sequoia range.

Work continues to restore resilience to sequoia groves

Although General Sherman’s clean bill of health is promising, California’s giant sequoias are hardly out of the woods. Increased beetle activity has been observed in several ancient groves, and sequoia stewards are concerned that accelerating climate change could spur greater losses from beetle attacks. High-intensity wildfires, which killed thousands of mature sequoias in 2020 and 2021, continue to pose an existential threat to these irreplaceable forests.

Land managers, scientists, and conservationists with the Giant Sequoia Lands Coalition (GSLC), including Save the Redwoods League, are already working to mitigate these grave threats to the forest. In the GSLC’s first two years alone, coalition members completed wildfire resilience work across half of California’s giant sequoia acres, planted more than 500,000 native seedlings in severely burned areas, and conducted scientific research to guide evidence-based restoration techniques. Researchers with the GSLC are also working to understand the extent of bark beetle infestations, what stressors make sequoias vulnerable to attack, and what can be done to protect the forest.

“The inspection conducted today is part of a much larger coordinated body of research to understand the changing ecology of these magnificent trees and take steps to address forest health collectively and strategically,” said Christy Brigham, chief of resources management and science for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Brigham noted the need to work together “to confront the challenges of climate change and restore natural fire processes to these Sierra Nevada landscapes so we can continue to enjoy them well into the future with future generations.”

One Response to “First climb of General Sherman Tree reveals health status”

Griff Griffith

Alarming topic, but thanks for doing the work to help the forest be more reslilient!